Now Reading: Second home investment in India: how serious capital is quietly reframing the decision

- 01

Second home investment in India: how serious capital is quietly reframing the decision

Second home investment in India: how serious capital is quietly reframing the decision

For affluent Indian families, the “second home” is no longer a simple lifestyle indulgence; it sits at the intersection of succession planning, global mobility, and portfolio construction. Rising domestic wealth, a structurally deeper mortgage market, and a visible NRI bid in key micro-markets have turned the question from “Can I afford it?” to “Does this earn its place in my capital stack?” In parallel, India’s prime residential values have compounded meaningfully since 2020, yet still screen at a discount to Dubai and Singapore on an absolute ticket-size basis in several luxury and ultra-luxury corridors, even as yields remain modest by global standards.

Sophisticated buyers have responded by treating second homes as either long-duration legacy assets or deliberately under-levered, low-volatility anchors alongside operating businesses and global financial portfolios. The result: second home investment in India can be compelling, but only when underwriting is done like any other large private asset — with clear intent, disciplined location risk, and a sober view on liquidity and taxation.

How India’s Prime Housing Fits into Global Capital Flows

The first post-pandemic cycle in Indian housing has been led not by speculation but by balance-sheet repair among developers and more conservative lending, even as end-user wealth has expanded sharply in the ₹4–₹10 crore bands in top cities. Knight Frank’s India Wealth Report 2023 and 2024 highlight that India’s UHNI population has been compounding in high single to low double digits annually, with residential real estate remaining a core allocation, though its share is slowly ceding ground to financial assets. In this context, the second home is increasingly evaluated against private credit, global equities, and offshore real estate rather than against a fixed deposit.

Relative to Dubai, Singapore, and London, India’s prime residential still offers lower entry prices for comparable built-up space in markets like peripheral Mumbai micro-markets, select Delhi NCR golf communities, and Bengaluru’s villa segments. Dubai continues to attract global capital on the back of zero personal income tax and highly liquid off-plan trading; Singapore and London retain their status as rule-of-law, institutional markets with strong tenant depth but high stamp duties for non-residents. India, by contrast, remains more idiosyncratic: regulatory protections have improved post-RERA and IBC, but execution risk, title diligence, and local governance still require a far higher degree of on-ground intelligence than in competing hubs.

What the Numbers Really Say about Second Homes

Across 2020–2024, multiple developer and brokerage reports point to robust absorption in India’s premium and luxury segments, particularly in Mumbai, Delhi NCR, Bengaluru, and select leisure markets like Goa. Knight Frank and Anarock commentary suggests double-digit annual price appreciation in many prime pockets post-2020, especially where supply had been constrained for several years and where developers focused on deleveraging rather than new land aggregation. Crucially, this has been accompanied by lower inventory overhang in the upper segments than in the mid-market in several cities, reflecting a depth of end-user demand among entrepreneurs, CXOs, and family offices.

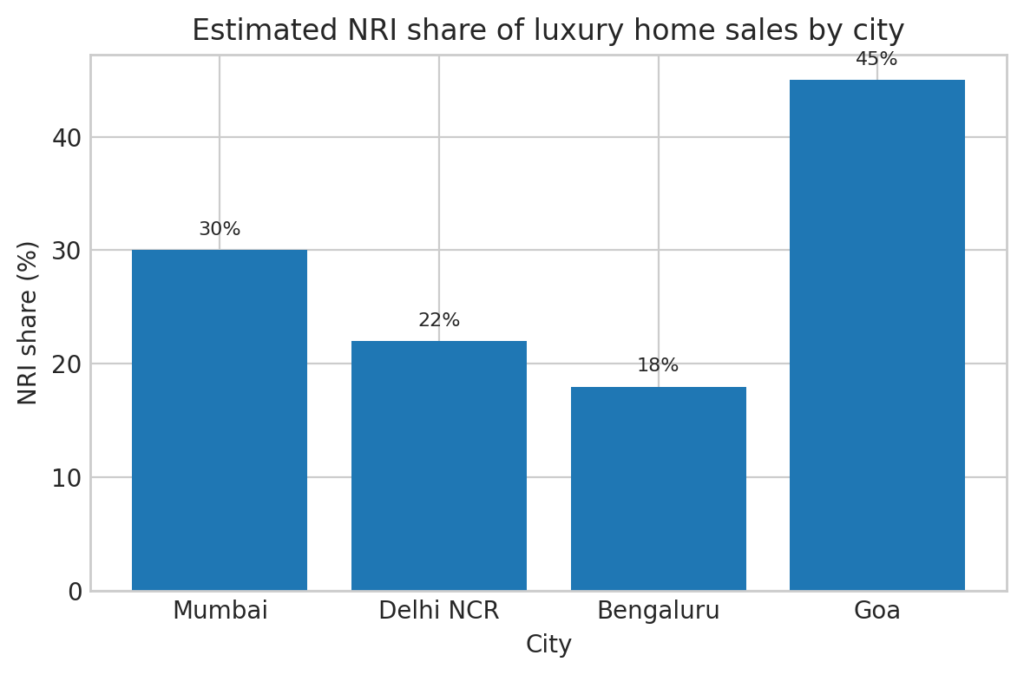

NRI participation has also become more visible in luxury and branded residences, especially in Mumbai, Pune, Bengaluru, Gurugram, and coastal Goa, aided by a weaker rupee over the last decade and the emotional pull of a high-quality “home base” in India. While exact shares vary by project and micro-market, it is common to see developers report 20–35% NRI contribution in well-located prime launches, with Goa and certain Mumbai micro-markets occasionally skewing higher. For serious investors, the signal is not the headline percentage but the profile: dollar and dirham earners treating Indian luxury real estate less as a trading asset and more as a long-term anchor.

NRI share in luxury residential transactions (selected cities)

NRIs have not been uniform buyers; their presence concentrates in specific micro-markets where lifestyle, connectivity, and brand comfort intersect.

Why Second Homes Matter Beyond Returns

For many first-generation wealth creators, the second home is less a pure investment and more a physical manifestation of having “arrived,” yet the decision is increasingly mediated by the next generation. The home doubles as a venue for multi-generational gatherings, a safe harbour in moments of political or global volatility, and a space that can flex between work, retreat, and hosting. This is pronounced in hill stations within driving distance of metros, coastal belts like North Goa, and self-contained townships on the edges of major cities.

At the same time, the second home often plays a quiet role in legacy architecture: held in a trust, it can serve as a non-financial asset allocated to specific branches of the family or earmarked as a future home for returning NRIs. For globally mobile heirs shuttling between India, the Gulf, Europe, and North America, a well-located Indian residence provides psychological and cultural anchoring, even if they hold more liquid exposure through offshore funds and equities. The key shift is intent: the savvier families are explicit about whether the second home is a “consumption plus legacy” asset or a “yield plus optionality” asset, and structure ownership, leverage, and tax planning accordingly.

Case studies: how serious investors are behaving

Mumbai: upgrading the primary, holding the legacy second

A Mumbai-based promoter family in their late 50s used the post-2020 equity market rally and a partial stake sale to upgrade from a 3-bedroom apartment in the western suburbs to a sea-facing 4-bedroom in South Mumbai, consolidating their primary residence into a more liquid, globally recognisable micro-market. The previous apartment, owned for over 15 years with a low historical cost base, was retained as a debt-free second home rather than sold, given its negligible marginal carrying cost and strong rental demand.

Over time, it has been informally “allocated” to a daughter working in private equity who intends to return to India within five years. This pattern — upgrading the primary while repurposing the previous home as a legacy second asset — is echoed in multiple Knight Frank and Anarock Mumbai-focused commentaries on wealth migration within the city’s micro-markets (see Knight Frank’s India Real Estate reports for 2022–2024 and Anarock’s Mumbai Market Watch series for context: https://www.knightfrank.co.in/research, https://www.anarock.com/research).

Delhi NCR: golf-side villas as controlled risk

In Gurugram, several family offices and senior executives have gravitated towards golf-course abutting villas and low-rise condominiums, treating them as controlled-risk second homes that balance lifestyle with reasonable liquidity. A typical allocation involves a ₹8–₹15 crore ticket, 50–60% equity-funded, with the balance through conservative leverage structured around visible cash flows.

Holding periods tend to be 7–10 years, with families valuing both the quality of community and the ability to host global guests in an environment that mirrors international standards. JLL and CBRE NCR market updates through 2023–2024 consistently highlight limited new supply in these gated, amenity-rich enclaves, which supports capital preservation even if headline yields remain in the low single digits (see https://www.jll.co.in/en/trends-and-insights/research and https://www.cbre.co.in/insights).

Bengaluru–Goa: operating business in one city, emotional anchor in another

A Bengaluru-based tech founder who recently exited part of his stake for a substantial liquidity event chose a two-pronged approach: a larger city home close to international schools and a separate second home in North Goa. The Bengaluru asset, in the ₹7–₹9 crore range, is explicitly viewed as a “living infrastructure” bet on the city’s continued technology and GCC growth.

The Goa home, purchased in the ₹4–₹6 crore band in a curated gated development, is positioned as a family retreat and eventual semi-retirement base, with low expectations on rental yield but strong belief in long-term land and scarcity value. Forbes India and Bloomberg have profiled similar founder behaviour, where coastal and hill second homes are funded largely in cash and held in family entities or trusts as intergenerational assets rather than trading positions (see https://www.forbesindia.com and Bloomberg’s India real estate features at https://www.bloomberg.com).

Takeaways for Allocating to a Second Home

- For NRI property investment in India, align city choice with likely future life patterns — children’s education, parental care, business interests — rather than chasing short-term yield differentials.

- Avoid over-concentration in a single developer or corridor; owning two assets in the same 2–3 km belt, even if they feel different, compounds micro-market risk without diversifying lifestyle.

- Use structures (trusts, LLPs, or Hindu Undivided Family where appropriate) to ringfence the second home within the broader family balance sheet and to pre-empt succession complexity, especially for globally dispersed heirs.

- Underwrite exit time, not just entry price: in ultra-luxury brackets, assume a 12–24 month realistic liquidity window and build your leverage and cash-flow planning around that, regardless of headline market sentiment.

Where the Second-Home Thesis Can Break

The primary risk with second homes in India is liquidity: ultra-luxury assets often have a thin buyer universe, and the bid can vanish quickly in periods of macro stress or policy uncertainty. Even in structurally strong micro-markets, transaction volumes can slow sharply, compressing effective exit valuations or elongating holding periods. Investors used to daily liquidity in public markets must internalise that a second home is, almost by design, a long-duration, lumpy exposure.

Regulatory and taxation complexity is another under-appreciated dimension. State-level stamp duties and registration charges, TDS on property transactions for NRIs, and capital gains rules across multiple jurisdictions can materially change net outcomes if not planned with professional advice. Over-concentration in marquee corridors — a single belt in North Goa, one golf-course community in Gurugram, or a very specific sea-facing stretch in Mumbai — can also backfire if civic infrastructure, policy attitudes, or local politics shift. Finally, there is an opportunity cost: capital locked in a second home is not available for compounding in scalable operating businesses or diversified global portfolios.

FAQs

How should NRIs think about buying a second home in India?

NRIs should align the purchase with long-term life plans — potential return timelines, parental care, children’s education, and tax residency — and structure ownership to minimise cross-border tax friction. Location, governance quality, and legal diligence matter more than short-term currency or price moves.

Is a second home in India a good investment right now?

It can be, but only if treated as a long-duration, low-liquidity asset with clear intent. Second homes in top Indian micro-markets have benefited from post-2020 price appreciation, yet they work best as legacy or lifestyle-led holdings rather than purely yield-driven investments.

What is a sensible budget allocation for a second home relative to net worth?

For UHNIs and well-capitalised founders, a second home is typically kept as a mid-single-digit percentage of net worth, sometimes rising into low double digits where there is strong legacy intent. The key is to avoid leverage that assumes rapid capital appreciation or quick exit.

Are rental yields attractive enough to justify a second home purely as an investment?

In most Indian luxury and ultra-luxury micro-markets, rental yields remain modest, often low single digits before tax and costs. The investment case usually rests on capital preservation, long-term appreciation, and non-financial utility rather than on income alone.

Where Second Homes Sit in the Next Decade of Indian Wealth

As India’s wealth architecture matures, the second home is shedding its image as a vanity purchase and emerging as a deliberate, if illiquid, building block in family balance sheets. For globally exposed Indian and NRI families, a well-chosen second home in India can sit alongside offshore funds, private equity, and operating businesses as a quiet, low-volatility store of value — provided location quality, governance, and succession are handled with institutional discipline.

Over the next decade, the most resilient outcomes are likely to accrue to those who buy less frequently but better: supply-constrained micro-markets, trustworthy developers, conservative leverage, and clear intergenerational intent. Families seeking to formalise this approach should consider commissioning private briefings or investor notes tailored to their specific city exposures, family structures, and cross-border obligations, before allowing any single second home to claim a permanent place in their global portfolio.