Now Reading: The 5-20-30-40 Rule Meets India’s Luxury Real Estate

- 01

The 5-20-30-40 Rule Meets India’s Luxury Real Estate

The 5-20-30-40 Rule Meets India’s Luxury Real Estate

India’s ultra-luxury housing market is behaving very differently from the rest of the residential ladder. Homes above ₹10 crore are being bought less as lifestyle upgrades and more as long-term anchors of family wealth. At the same time, a simple framework that once guided salaried homebuyers is quietly reappearing in conversations inside family offices and among NRIs: the 5-20-30-40 rule.

The original idea was straightforward: do not let a home loan take over your balance sheet or your life. Today, in a world of ₹10–50 crore apartments, multi-country portfolios, and children educated abroad, the same rule has evolved into something else—an internal discipline system for illiquid, legacy assets.

This piece looks at how that framework translates when the “home” in question is a Worli sea-facing apartment, a Camellias-level residence in Gurugram, a Bengaluru penthouse, or a villa in Assagao.

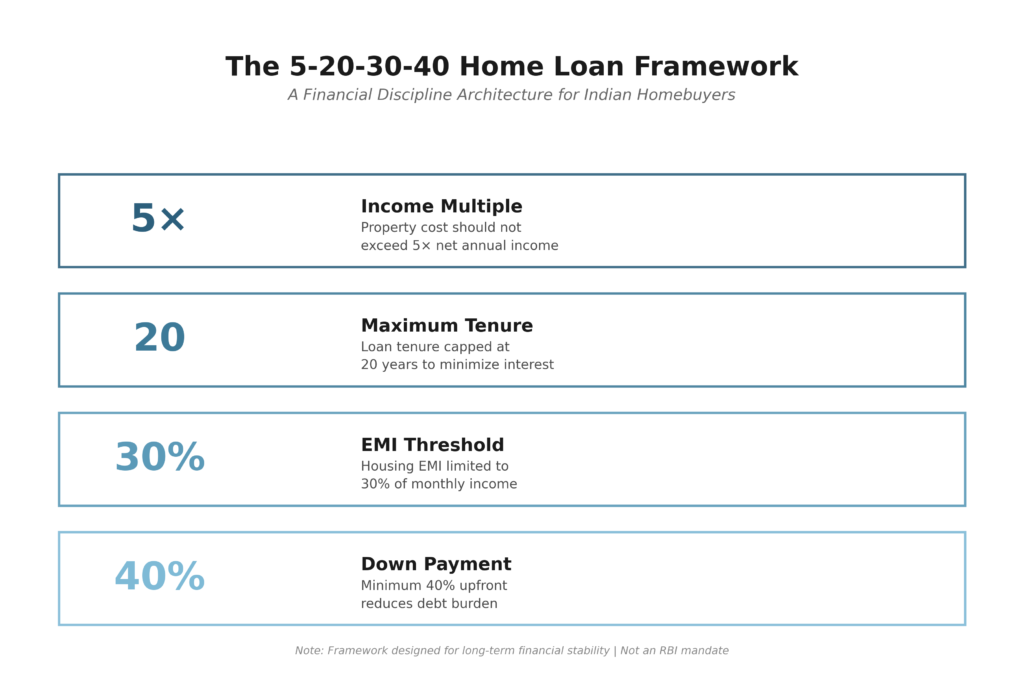

The 5-20-30-40 Rule: The Short Version

In its classic form, the 5-20-30-40 rule says:

- 5× – The property price should not exceed five times your annual take-home income.

- 20 – Keep the loan tenure within 20 years.

- 30% – Restrict home loan EMIs to 30% of your monthly income.

- 40% – Put down at least a 40% down payment from own funds.

It was never a regulation. It emerged from planners and risk managers who had seen too many households stretch into 25–30 year loans, only to be exposed when interest rates moved up or income growth stalled.

For upper-middle income buyers it was a safety net. For UHNIs and NRIs today, the numbers themselves often look trivial. A family with ₹50–100 crore net worth can easily write a cheque for a ₹10 crore home. The reason the framework still matters is different: it imposes structure in a part of the portfolio that is large, emotional, and slow to exit.

India’s Luxury Cycle in a Global Frame

Post-pandemic, India has moved into a distinct affluence cycle. A decade ago, Dubai and Singapore were the default offshore playgrounds for regional wealth; London was the aspirational address. Those three markets remain important, but the conversation inside Indian families has shifted.

Three structural forces anchor that shift:

- Wealth creation at home

India’s UHNI cohort has expanded sharply, with more founders, next-generation promoters, and tech professionals moving into the ₹50–500 crore wealth band. Residential allocations of 20–25% of net worth are common, with a significant share now staying onshore. - Premiumisation of domestic housing

In the top metros, homes above ₹1 crore have gone from niche to mainstream in just a few years. The ₹5–10 crore band is now a “new comfort” zone for many senior corporate and entrepreneurial families. The ₹10 crore+ segment, once confined to South Mumbai and Lutyens’ Delhi, now has depth in parts of Gurugram, Bengaluru, and coastal Goa. - India as a “home base” in global portfolios

For NRIs and OCIs in the US, UK, Middle East or Singapore, India is no longer just a sentimental add-on. A Mumbai or Delhi NCR home is now part of a deliberate global architecture: one leg in a tax-efficient hub, one in an education hub, and one in India as the family anchor.

Within that landscape, the question is less “Can this home be afforded?” and more “How should this home be financed so it doesn’t distort the rest of the portfolio?”

Reframing 5-20-30-40 for ₹10 Crore+ Buyers

At higher ticket sizes, the raw numbers behind the rule change. The logic does not.

5× Becomes 20–25% of Net Worth

For a ₹12 crore property, a strict 5× income multiple is almost meaningless for a promoter or founder whose cash flow swings with business cycles. In practice, the disciplined families tend to think in terms of net worth allocation, not salary multiples.

A quiet internal rule of thumb has emerged:

- Primary luxury home – keep it within 20–25% of investable net worth.

- Second / third homes – avoid pushing total residential exposure above 30–35%, unless there is a clear, thought-through legacy or consolidation plan.

It is a simple filter. If a ₹20 crore home is on the table for a family with ₹40 crore net worth, something is off. If the same home is on the table for a family with ₹150 crore, it may be entirely reasonable—provided leverage is sensible.

20-Year Tenure: Interest Cost and Optionality

On paper, lenders are happy to stretch home loans to 25–30 years, sometimes longer for younger borrowers. At scale, this looks cheap: a lower EMI, more “headroom”.

In practice, the 20-year ceiling does three useful things for wealthier borrowers:

- It caps interest leakage. On a large loan, the difference in total interest between 20 and 30 years runs into multiple crores.

- It forces a hard stop before or around retirement, when family income may diversify but individual income can taper.

- It preserves optionality. If a liquidity event or exit opportunity appears 7–10 years down the line, the outstanding debt is meaningfully lower.

Many UHNIs now work with an internal plan where the formal tenure is 20 years, but the intended tenure is 12–15 years, using bonuses, business cash flows or secondary exits to prepay aggressively in the early years.

30% EMI: Protecting Cash Flow, Not Affordability

The traditional reading is “do not spend more than 30% of monthly income on home EMIs.” For a family with ₹4–5 crore annual cash inflows, this is rarely binding.

Where the rule still bites is when all obligations are added up:

- Home loan EMIs

- Existing business or property loans

- Education loans (often dollar-linked)

- Car and lifestyle-linked financing

The more conservative families now track a blended ratio: all EMIs within 35–40% of stable, recurring income, and home EMIs alone within 25–30%. The reason is simple: this preserves room for:

- Ongoing investments into operating businesses

- Equity and AIF commitments

- Insurance and long-term health care provisioning

- Unplanned family or business support

For NRIs, this threshold is also a currency risk buffer. A home loan serviced from overseas income looks different if the rupee suddenly strengthens and reduces the foreign currency surplus.

40% Down Payment: Equity as Shock Absorber

In a rising market, high leverage looks clever. In a flat or choppy market, it can trap capital.

A 40–50% down payment does three quiet but important jobs:

- It absorbs price corrections or soft patches without pushing the asset into negative equity.

- It reduces psychological pressure to “do something” with the property just to service the loan.

- It strengthens the family’s hand with both banks and developers—often leading to slightly better pricing, better inventory, and smoother execution.

Especially in thinner luxury markets like Goa or selective micro-pockets of Bengaluru and NCR, this equity cushion is the difference between being able to ride out a slow two-year patch and being forced to sell into a weak bid.

NRI Capital: Four Cities, Four Behaviours

For NRIs and OCIs, the 5-20-30-40 framework often intersects with very specific city-level intent.

- Mumbai is where many families want their long-term India base—even if they live abroad for decades. The acquisition is usually a primary or future-primary home, with little urgency to monetise. Discipline here is about not letting a single apartment consume a disproportionate share of the global portfolio.

- Delhi NCR has seen a re-rating in ultra-luxury. For NRIs, it is often about family proximity and status neighbourhoods. Golf Course Road or the newer ultra-luxury projects in Gurugram are purchased as multi-decade anchors. Leverage decisions are typically made at family balance sheet level, not borrower level.

- Bengaluru continues to draw NRIs in technology and global capability roles. Whitefield, Outer Ring Road, and select villa communities see a mix of future-return plans and yield-plus-appreciation logic. Here, the EMI-to-rent gap matters more, and a stricter version of the 30% and 40% rules tends to make sense.

- Goa, especially villages like Assagao, Parra and parts of coastal North, is now a serious line item in portfolios rather than a whimsical holiday home. The best-behaved capital here is equity-heavy and patient.

In every case, the question sophisticated NRI buyers are asking is less “Can the bank fund this?” and more “If global conditions turn, does this exposure still feel comfortable?”

Three Quiet Vignettes

These are composites drawn from real transactions and patterns across advisors, not single identifiable families. The numbers are indicative, not prescriptive.

1. The Mumbai Founder

A mid-40s founder exits a business and nets ₹300+ crore after tax. He buys a ₹18 crore Worli apartment. Instead of paying cash, he writes a cheque for ₹9 crore and takes a 15–18 year loan on the rest, keeping personal EMIs well under 10% of his recurring investment income.

His logic is blunt: the portfolio can reasonably compound in the low double digits; the mortgage will cost high single digits. The spread, over time, pays for a meaningful part of the home. What keeps this from being reckless is that the property still sits under 25% of net worth, the tenure fits his age and risk appetite, and there is no dependence on salary income to service the loan.

2. The Bengaluru Return Plan

An NRI couple in their early 50s working in the US buys a ₹6 crore 4BHK in Bengaluru. They intend to move back in 8–10 years. They put down roughly half, keep the loan to 15–16 years, and let the property out in the interim.

Their focus is less on maximising yield and more on locking in a future lifestyle at today’s prices, while ensuring that the loan would still be entirely manageable even if one income disappears or the rupee-dollar equation moves against them. For them, the framework is essentially a stress test.

3. The Goa Villa as a Legacy Asset

A family office with ₹500 crore-plus under management acquires a villa in Goa for around ₹10–12 crore. The intent is multi-generational: a place where children and grandchildren can gather, not a financial instrument to be optimised every quarter.

Here, high equity and a contained tenure are part of the same instinct that drives conservative leverage in the operating businesses. The villa is designed to never become a forced-sale candidate, regardless of business cycles.

The Risks Thoughtful Investors Actually Worry About

The list is not long, but each item is material:

- Regulation and paperwork

RERA has improved transparency, but title clarity, land use, and environmental approvals still need real scrutiny. For NRIs, FEMA and tax rules around repatriation add another layer. This is unglamorous work, but it is exactly where future headaches are either avoided or baked in. - Liquidity through cycles

In buoyant years, ultra-luxury assets appear more liquid than they are. In plateau years, even the best addresses can take 12–18 months to find the right buyer at a sensible price. The families that sleep well are the ones who structure their leverage on the assumption that they may have to hold through at least one slow cycle. - Overconcentration in a single market

It is increasingly common to see families with 40–50% of their net worth tied up in Indian real estate, often within a single metro. That may work exceptionally well in some scenarios, but it leaves little room for policy surprises, localised oversupply, or shifts in how the next generation wants to live.

The 5-20-30-40 rule does not solve these risks. What it does, if followed thoughtfully, is reduce the odds of being forced into bad decisions at the wrong time.

Where Disciplined Capital Is Moving Now

In conversations with advisers and allocators, five patterns recur:

- Using leverage selectively, not reflexively

Debt is being used where it improves overall portfolio outcomes, not simply because it is available. A 20-year ceiling and clear prepayment plan are now common asks. - Focusing on micro-markets rather than city labels

Within Mumbai, Delhi NCR or Bengaluru, capital is becoming more micro-selective: specific corridors, specific developers, specific projects where governance and delivery track record justify long holds. - Separating “global lifestyle” from “India anchor” assets

Dubai and Singapore may serve tax and mobility functions. London may serve education needs. India serves continuity and legacy. Financing and holding logic are being tailored accordingly, rather than treated as a single real estate “bucket”. - Documenting family-level rules

Some families now treat 5-20-30-40 as a starting point for written internal policies: maximum property concentration, maximum leverage by age, minimum liquidity buffers, and clear principles on when to sell versus when to hold through cycles. - Treating the next generation as stakeholders, not passengers

Heirs in their 20s and 30s, often educated and working abroad, are being included earlier in these decisions. For them, the question is not just “what do we own?” but “how flexible is this architecture if our lives look different from yours?”

FAQs

What is the 5-20-30-40 rule for home loans in India?

The 5-20-30-40 rule is a simple discipline framework for borrowing. It suggests buying a home priced at up to 5× your annual take-home income, keeping loan tenure within 20 years, limiting EMIs to 30% of your monthly income, and putting at least 40% as down payment. It is not an RBI rule, but a prudential guideline to avoid over-leverage.

How does the 5-20-30-40 rule apply to ₹10 crore+ luxury homes?

For luxury homes, the 5× income idea is usually adapted to net worth. Many UHNIs cap a single property at around 20–25% of investable net worth, keep tenure under 20 years, and still target 30% EMI and 40–50% equity. The goal is not affordability but ensuring one asset does not dominate the balance sheet.

What is a prudent down payment for a luxury property in India?

A 40–50% down payment is usually sensible for primary luxury homes, and 50–60% for pure investment properties. This equity cushion protects you if prices stagnate or correct and reduces pressure to sell in a weak market. It also strengthens your position with both lenders and developers.

How much EMI is considered safe for HNI or NRI buyers?

Keeping home EMIs within 25–30% of stable monthly income is a good benchmark, even at higher wealth levels. When all EMIs are added together—home, business, car, education—they should ideally stay within 35–40% of income. NRIs should also stress-test EMIs for currency swings and potential job or bonus volatility.

What risks does the 5-20-30-40 rule help manage in luxury real estate?

The rule mainly guards against over-leverage, long debt overhang, and liquidity stress. In India’s luxury segment—where exits can take 12–18 months and regulation is complex—it reduces the chance of forced sales, protects cash flow during slow cycles, and keeps room for other investments and family obligations.

A Short Conclusion

In the middle of a strong luxury cycle, it is easy to forget how quickly sentiment and liquidity can change. The 5-20-30-40 rule will not appear in any RBI circular. It will not show up in glossy marketing decks. It tends to live in quieter places: family office memos, credit committee notes, side conversations between founders and their advisors.

Its core message is almost unfashionably simple: keep leverage modest, tenures contained, EMIs proportionate, and equity meaningful.

In a market where a single apartment can represent decades of compounded work, that kind of simplicity is not a constraint. It is a form of respect—for capital already earned, and for the generations expected to live with the assets created today.